August 25, 2016

Data to action: Can we use mobile apps to reverse systematic educational failures in West Africa?

By Anthony Olorunnisola, Pennsylvania State University, and Akshaya Sreenivasan, Texas A&M University

Popularly referred to as the “champion of the disadvantaged,” the Comprehensive High School Aiyetoro in Ogun State in southwest Nigeria was one of the first schools established after independence. The school boasts a strong alumni that includes high ranking government officials and businessmen. Today, according to recent rankings, the school is not among the top 1,000 ranked schools in the nation.

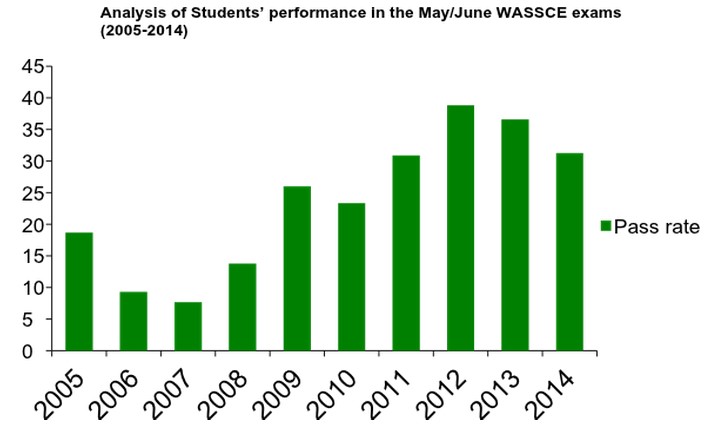

Over the years, the school witnessed a steady increase in failure rates among graduating students. This trend is similar across public, private, faith-based and single-gender schools in Nigeria (see Figure 1). In the last decade alone, between 80 and 85 percent (or about 1.25 million) Nigerian senior secondary school graduates have failed the West African Examination Council (WAEC) examinations each year—especially in foundational subjects like mathematics and English. We consider this persistent outcome as equivalent to a systemic failure with every stakeholder group a contributor.

Figure 1: Overall failure rate among students in Nigeria

Figure 1: Overall failure rate among students in Nigeria

Source: National Competitiveness Council (NCCN), Nigeria

We developed a systematic approach using a painstaking and deliberative evaluation of roles played by different stakeholders in the secondary education system. In the summer of 2012, we mapped popular parallel educational practices worldwide. Our goal was to develop geo-local solutions that can be scalable to countries that enroll students in WAEC exams.

During a sabbatical year in 2013/14 and subsequent visits to Nigeria during 2015 summer, we conducted interviews with numerous stakeholders (students, parents, teachers, school administrators, state-run education agencies, book publishers and WAEC officials) and engaged with secondary education across six states of southwest Nigeria. More than 100 hours of transcribed interviews and surveys created the body of knowledge that has aided in identifying proposed solutions.

Driven by data, we have identified two solutions:

One is to develop Regimen, a self-assessment mobile application that will potentially provide West African students with complementary testing methods in core subjects that include English and mathematics. With the adoption of mobile phones at the level of popular penetration in Nigeria (138 million units in a population of 130 million), we would like to make this application available across different platforms, at affordable rates or free and, most importantly, student-friendly.

A second solution is After School, which are video lessons in English and mathematics to be delivered by teachers of West African extraction who are familiar with the WAEC curriculum. Subject experts are teachers located in schools where students’ performance fare better than national average and others with expertise in the respective subjects.

With funds from the Arthur W. Page Center, we will develop pilot versions of the two solutions within the next year and set the machinery in motion for beta testing both solutions. We hope that the success of our tests will provide the leverage needed for procuring external funding in support of the solutions’ roll-out across West Africa. The core value enshrined in the Page Center’s ethos – advancing ethics and promoting responsible communications – will undoubtedly be furthered as this project moves onward.

To learn more about the project, please contact Anthony Olorunnnisola at axo8@psu.edu.